NY Times

Also Seeing Life Through a Face Mask

Tom Uhlman for The New York Times

Tom Uhlman for The New York Times

"I like to hit people," Holley Mangold said about playing football.

By KAREN CROUSE

Published: October 29, 2006

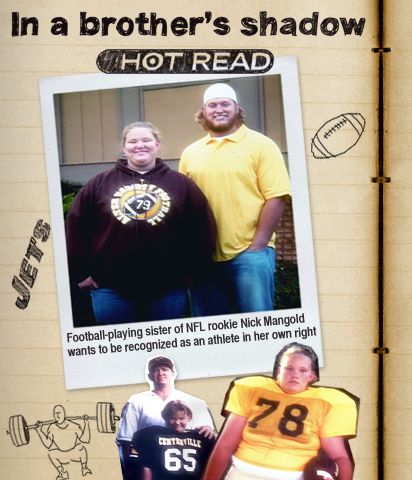

CENTERVILLE, Ohio, Oct. 28 ? Nick Mangold, a 6-foot-4, 300-pound rookie starting center for the Jets, is not the only football player in his family. His 16-year-old sister, Holley, a backup on the offensive line at Archbishop Alter High School, played on special teams Friday night during the Knights? 33-15 victory against their archrival, Chaminade-Julienne.

Robert Caplin for The New York Times

Robert Caplin for The New York Times

Nick Mangold is a first-round draft pick who has started all seven games for the Jets.

Ed Domsitz, the high school coach of both Mangolds, said, ?Holley might be a tad meaner.?

Mr. Domsitz said her size, technique and tenacity had allowed Holley to compete at this level. She is on track to earn a varsity letter in football as a junior this year. ?She?s an in-your-face, knock-you-on-your-tail offensive lineman,? Mr. Domsitz said.

Holley?s father, Vern Mangold, said she was the state?s first high school girl to play a down from scrimmage. At 5-9 and 310 pounds, she is an imposing presence on a team with only a couple of other players that size.

Off the field, Holley carries herself with the aplomb of a runway model. She strolled into the school secretary?s office for an interview after a gym class this week, wearing brown sweat pants and a black collared Alter High shirt, with her shoulder-length blond hair in a ponytail. Her fingernail polish was burgundy.

Holley has the outgoing personality of a cheerleader, and Mr. Domsitz tried to steer her in that direction when she was in the second grade and showed up at his summer youth football camp for the first time. Over the years, it became a running joke between them; she would show up for football camp, and he would point out where the cheerleaders were practicing.

Holley laughed at the suggestion that she had changed Mr. Domsitz?s mind about girls playing football. ?I would say that Coach Domsitz is a traditional guy,? she said. ?He believes, just like my father and my brother did, that football is not a sport for girls.?

She added: ?I don?t think I?ve clearly won him over. I think he?s warming up to the idea.?

Mr. Mangold has also overcome his initial objections. He stood in the last row of the home bleachers in a steady rain Friday, without an umbrella, and cheered for Holley, whom he affectionately calls ?my little buttercup,? every time she stuffed her ponytail into her helmet and trotted onto the field.

?She plays the game well,? he said. ?That?s more surreal, actually, than what Nick?s doing.?

On Sunday, Holley will accompany her parents, Vern and Therese, to Cleveland Browns Stadium to watch Nick, her 22-year-old brother, play in his first professional game in his home state.

Nick Mangold has been Holley?s guiding influence for as long as she can remember, since he got down on his knees and played Nerf football with his sisters in the front yard. Kelley, 19, is a freshman swimmer at Agnes Scott College outside Atlanta. Maggey, the youngest, is 7.

?Just like any sibling,? Holley said, ?I wanted to do the same thing my big brother did.?

Her brother?s approval means more to Holley than almost anybody else?s, and in the emotionally charged realm of sibling relationships, her participation in football has created additional sparks.

?I?m perfectly fine with that,? she said. ?Maybe he doesn?t support the idea of girls playing football, but anything I?ve done he has always supported me.? She added, ?A lot of guys who haven?t been my teammates, they will never understand, including Nick.?

Nick Mangold acknowledged that he was torn. ?You know, I?m supportive of her and what she does, but I don?t know how I would handle it if I was one of her teammates,? he said Friday in a telephone interview.

?Definitely there?s a pride factor as her older brother,? he added. ?It?s a neat thing what she?s doing. But, um, you know, she?s been playing since the second grade, so really for the family it?s become pretty normal. I never really think about what she?s doing.?

Nick Mangold, a three-year starter at Ohio State before the Jets drafted him in the first round, with the 29th pick, has made a seemingly effortless transition to the pros, starting his first seven games and incurring only one penalty.

Holley cannot say she is surprised. From honors algebra to blocking human eclipses of the sun like Ted Washington, the Browns? 6-5, 365-pound nose tackle, Nick Mangold has seemed to ace every assignment.

?It?s horrible to follow in his footsteps,? she said, ?because he?s one of those big brothers where everything he does, he does really well.?

She added: ?If I had Nick?s work ethic, I?d be amazing right now. God gave me a lot of natural strength, but I have a problem with laziness.?

Holley says she attracts a double team of attention as a girl on the offensive line whose brother is an N.F.L. lineman.

?Sometimes I?ve got to look back and say I?m getting compared to a guy that played Division I and is in the pros,? she said. ?I?m going to look bad because I?m not as good as he is.?

Holley has tried 11 sports, by her count, including swimming, softball and roller skating. Only football has held her passion. ?I like to hit people,? she said.

As Holley advanced through the youth football ranks, people who were following her progress needled Mr. Domsitz good-naturedly. ?Are you ever going to let a girl play on the team?? they said. Laughing, Mr. Domsitz would tell them no.

Skip to next paragraph

The Mangold Family

The Mangold Family

A family photograph of the Mangold children, from left, Holley, 5; Kelley, 7; and Nick 11. Nick plays for the Jets, and Kelley is a swimmer.

Holley gave him no choice, really. Like a lot of boys in Kettering, a Dayton suburb, she grew up dreaming of playing on Friday nights in front of sellout crowds. High school football in central Ohio is the connective tissue that binds communities, and spots on the team are prized.

Alter High has a student body of 700, roughly half of which is male, but it had no trouble finding 100 players to fill out the freshman, junior varsity and varsity football squads. In addition to her special-teams duties, Holley estimated that she played 20 downs from scrimmage during the 10-0 regular season, the Knights? first unbeaten and untied team.

The first time she ran onto the field with the offense in a varsity game, on the first Friday in September, she said: ?Our whole fan section went crazy. It was probably one of the best moments I?ve had in football.?

It is big challenge for Holley to block out the messages of a culture that celebrates the size 0 female figure. Players on the offensive line generally do not get much notice, but she sticks out.

?I can?t say that it never bothers me what people think of me,? Holley said. ?So many people judge me that I don?t even care anymore.?

The girls at her school are supportive, Holley said, but she spends most of her time with the football players, calling them ?my second family.? Her teammates, she said, have nicknamed her Den Mother, and she calls them her brothers.

Last month, Holley attended the Jets? season opener at Tennessee. Afterward, when she saw her brother in the tunnel outside the visiting locker room, she said, ?I kind of bragged to him that I got into a game and got to play.?

He did not say much in response. ?Being the older brother, you have to keep things grounded,? he said. ?I play that card a lot, not really giving her every pat on the back, making sure she?s paving her own way.?

Also Seeing Life Through a Face Mask

"I like to hit people," Holley Mangold said about playing football.

By KAREN CROUSE

Published: October 29, 2006

CENTERVILLE, Ohio, Oct. 28 ? Nick Mangold, a 6-foot-4, 300-pound rookie starting center for the Jets, is not the only football player in his family. His 16-year-old sister, Holley, a backup on the offensive line at Archbishop Alter High School, played on special teams Friday night during the Knights? 33-15 victory against their archrival, Chaminade-Julienne.

Nick Mangold is a first-round draft pick who has started all seven games for the Jets.

Ed Domsitz, the high school coach of both Mangolds, said, ?Holley might be a tad meaner.?

Mr. Domsitz said her size, technique and tenacity had allowed Holley to compete at this level. She is on track to earn a varsity letter in football as a junior this year. ?She?s an in-your-face, knock-you-on-your-tail offensive lineman,? Mr. Domsitz said.

Holley?s father, Vern Mangold, said she was the state?s first high school girl to play a down from scrimmage. At 5-9 and 310 pounds, she is an imposing presence on a team with only a couple of other players that size.

Off the field, Holley carries herself with the aplomb of a runway model. She strolled into the school secretary?s office for an interview after a gym class this week, wearing brown sweat pants and a black collared Alter High shirt, with her shoulder-length blond hair in a ponytail. Her fingernail polish was burgundy.

Holley has the outgoing personality of a cheerleader, and Mr. Domsitz tried to steer her in that direction when she was in the second grade and showed up at his summer youth football camp for the first time. Over the years, it became a running joke between them; she would show up for football camp, and he would point out where the cheerleaders were practicing.

Holley laughed at the suggestion that she had changed Mr. Domsitz?s mind about girls playing football. ?I would say that Coach Domsitz is a traditional guy,? she said. ?He believes, just like my father and my brother did, that football is not a sport for girls.?

She added: ?I don?t think I?ve clearly won him over. I think he?s warming up to the idea.?

Mr. Mangold has also overcome his initial objections. He stood in the last row of the home bleachers in a steady rain Friday, without an umbrella, and cheered for Holley, whom he affectionately calls ?my little buttercup,? every time she stuffed her ponytail into her helmet and trotted onto the field.

?She plays the game well,? he said. ?That?s more surreal, actually, than what Nick?s doing.?

On Sunday, Holley will accompany her parents, Vern and Therese, to Cleveland Browns Stadium to watch Nick, her 22-year-old brother, play in his first professional game in his home state.

Nick Mangold has been Holley?s guiding influence for as long as she can remember, since he got down on his knees and played Nerf football with his sisters in the front yard. Kelley, 19, is a freshman swimmer at Agnes Scott College outside Atlanta. Maggey, the youngest, is 7.

?Just like any sibling,? Holley said, ?I wanted to do the same thing my big brother did.?

Her brother?s approval means more to Holley than almost anybody else?s, and in the emotionally charged realm of sibling relationships, her participation in football has created additional sparks.

?I?m perfectly fine with that,? she said. ?Maybe he doesn?t support the idea of girls playing football, but anything I?ve done he has always supported me.? She added, ?A lot of guys who haven?t been my teammates, they will never understand, including Nick.?

Nick Mangold acknowledged that he was torn. ?You know, I?m supportive of her and what she does, but I don?t know how I would handle it if I was one of her teammates,? he said Friday in a telephone interview.

?Definitely there?s a pride factor as her older brother,? he added. ?It?s a neat thing what she?s doing. But, um, you know, she?s been playing since the second grade, so really for the family it?s become pretty normal. I never really think about what she?s doing.?

Nick Mangold, a three-year starter at Ohio State before the Jets drafted him in the first round, with the 29th pick, has made a seemingly effortless transition to the pros, starting his first seven games and incurring only one penalty.

Holley cannot say she is surprised. From honors algebra to blocking human eclipses of the sun like Ted Washington, the Browns? 6-5, 365-pound nose tackle, Nick Mangold has seemed to ace every assignment.

?It?s horrible to follow in his footsteps,? she said, ?because he?s one of those big brothers where everything he does, he does really well.?

She added: ?If I had Nick?s work ethic, I?d be amazing right now. God gave me a lot of natural strength, but I have a problem with laziness.?

Holley says she attracts a double team of attention as a girl on the offensive line whose brother is an N.F.L. lineman.

?Sometimes I?ve got to look back and say I?m getting compared to a guy that played Division I and is in the pros,? she said. ?I?m going to look bad because I?m not as good as he is.?

Holley has tried 11 sports, by her count, including swimming, softball and roller skating. Only football has held her passion. ?I like to hit people,? she said.

As Holley advanced through the youth football ranks, people who were following her progress needled Mr. Domsitz good-naturedly. ?Are you ever going to let a girl play on the team?? they said. Laughing, Mr. Domsitz would tell them no.

Skip to next paragraph

A family photograph of the Mangold children, from left, Holley, 5; Kelley, 7; and Nick 11. Nick plays for the Jets, and Kelley is a swimmer.

Holley gave him no choice, really. Like a lot of boys in Kettering, a Dayton suburb, she grew up dreaming of playing on Friday nights in front of sellout crowds. High school football in central Ohio is the connective tissue that binds communities, and spots on the team are prized.

Alter High has a student body of 700, roughly half of which is male, but it had no trouble finding 100 players to fill out the freshman, junior varsity and varsity football squads. In addition to her special-teams duties, Holley estimated that she played 20 downs from scrimmage during the 10-0 regular season, the Knights? first unbeaten and untied team.

The first time she ran onto the field with the offense in a varsity game, on the first Friday in September, she said: ?Our whole fan section went crazy. It was probably one of the best moments I?ve had in football.?

It is big challenge for Holley to block out the messages of a culture that celebrates the size 0 female figure. Players on the offensive line generally do not get much notice, but she sticks out.

?I can?t say that it never bothers me what people think of me,? Holley said. ?So many people judge me that I don?t even care anymore.?

The girls at her school are supportive, Holley said, but she spends most of her time with the football players, calling them ?my second family.? Her teammates, she said, have nicknamed her Den Mother, and she calls them her brothers.

Last month, Holley attended the Jets? season opener at Tennessee. Afterward, when she saw her brother in the tunnel outside the visiting locker room, she said, ?I kind of bragged to him that I got into a game and got to play.?

He did not say much in response. ?Being the older brother, you have to keep things grounded,? he said. ?I play that card a lot, not really giving her every pat on the back, making sure she?s paving her own way.?